Downloads

Priority 10: Leverage More Adequate and Equitable School Funding

COVID-19’s impact on our economy has been unprecedented: Since mid-March, one in five employed Americans has either temporarily or permanently lost their jobs. The downturn in our economy has dramatically impacted state revenue: According to the most recent estimates by the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, state revenue shortfalls will likely reach about 10% in the current year and more than 25% in the next. On top of this, states are facing additional costs related to health care, unemployment, and education. Even conservative estimates of state funding cuts to schools suggest that states will need between $200 billion and $300 billion to stabilize their k–12 education budgets over the next year and a half. Because states cannot engage in deficit spending, and education accounts for a large share of state budgets, substantial cuts are inevitable without federal assistance.

These budget reductions are coming at a time when school districts and early childhood programs are also seeing increased costs because of COVID-19, including additional costs for providing devices and connectivity for distance learning, resources for expanded learning time, and additional food services for students from low-income families and students with special needs; costs to meet COVID-19 health and safety guidelines; and costs for additional staff to support physical distancing. Altogether these costs could total $370 billion over the coming year.

The communities most impacted by these budget shortfalls are those that serve the students from low-income families and students of color who have been and will be most affected by the health, employment, and housing impacts of COVID-19. Prior to the pandemic, school districts serving the largest proportions of Black, Latino/a, and Native American students already received about $1,800 less per pupil than those serving the fewest students of color. Declines in state revenue and increased costs will disproportionately hit schools in communities with high proportions of students from low-income families and low property wealth, which rely more on state education funding from sales and income taxes than on more stable local property taxes, thus furthering the divide.

This is because the United States’ reliance on local revenues has produced one of the most unequal school funding systems in the industrialized world. Despite strong evidence that money matters for student achievement and other important life outcomes, especially for students from low-income families, relatively few states have yet redesigned their systems to create more adequate and equitable funding. Those that have made such changes show much stronger outcomes.

Without a determined effort to produce a different outcome, funding cuts made to education now could be as long-lasting as they were during and after the Great Recession. While we are now several years removed from the end of the last recession, we still have 40,000 fewer public school teachers than we did in 2008 (see Figure 10.1).

Data source: U.S. Department of Education, National Center on Education Statistics.

Furthermore, with the exception of those few states that seized the moment to transform their funding systems, school resources became more inequitable over that period of time.1 However, as we describe below, states such as California and Rhode Island used the event of the recession to create new funding formulas that were designed to distribute funds more equitably as resources returned to the system—and they emerged from that era with more equitable and higher-performing systems. This is something that both federal and state policymakers should be considering as they take a long view to the years ahead.

What Students Need

Even before COVID-19, most state education finance systems were not working for students from low-income families, students of color, and those with a range of needs—many of which are exacerbated in high-poverty communities where food and housing insecurity, lack of health care, and inadequate community services are commonplace. Given the great inequalities in our society, including the highest rates of child poverty in the industrialized world, schools should be providing more intensive services for children in high-poverty areas than in more affluent areas. However, the opposite is true. In most states, districts serving affluent students receive as much or more money than those serving children in poverty, and only a handful have funding systems that provide resources that are both adequate and equitable.

Funding inequities are even more apparent when it comes to access to high-quality early learning. Based upon the Transforming the Financing of Early Care and Education consensus study report, early childhood programs only received approximately 37% of the public funding estimated to be needed to provide high-quality care and education to children. As a result, the burden to cover the costs falls upon parents, an expense few can afford. Due to the lack of affordability, too few infants of working families have access to the early care and education they need, and just 53% of 3- to 5-year-olds attend preschool—making the United States an outlier among economically developed countries.

Without robust public funding, programs often operate on shoestring budgets, with teachers paid one third to one half as much as their k–12 colleagues. The COVID-19 pandemic threatens to set our early childhood education system back even further financially. State-subsidized early education programs are likely to take dramatic hits, given current projections for major decreases in state funding, and private pre-k programs may close permanently due to increased costs and decreased revenue. The combination could mean the loss of up to 4.5 million child care slots, according to one estimate.2 Part of what makes state early childhood education budgets so vulnerable is that early childhood programs rely on a patchwork of funding streams to make ends meet, many of which are vulnerable to cuts in bad economic times.

Students who live in poverty, those who are homeless or in foster care, those who are English learners, and those with learning disabilities cost more to educate and should be recognized in school funding formulas with greater per-pupil spending weights. And districts with concentrations of such pupils carry more responsibility to provide wraparound services and intensive teaching and learning opportunities, which need to be recognized in school funding systems as well. Until the United States repairs its tattered safety net for children, so that poverty, hunger, and housing instability are not constant companions for many young people, it should fund their schools and early childhood programs at much higher rates and in more purposeful ways to support their healthy learning and development.

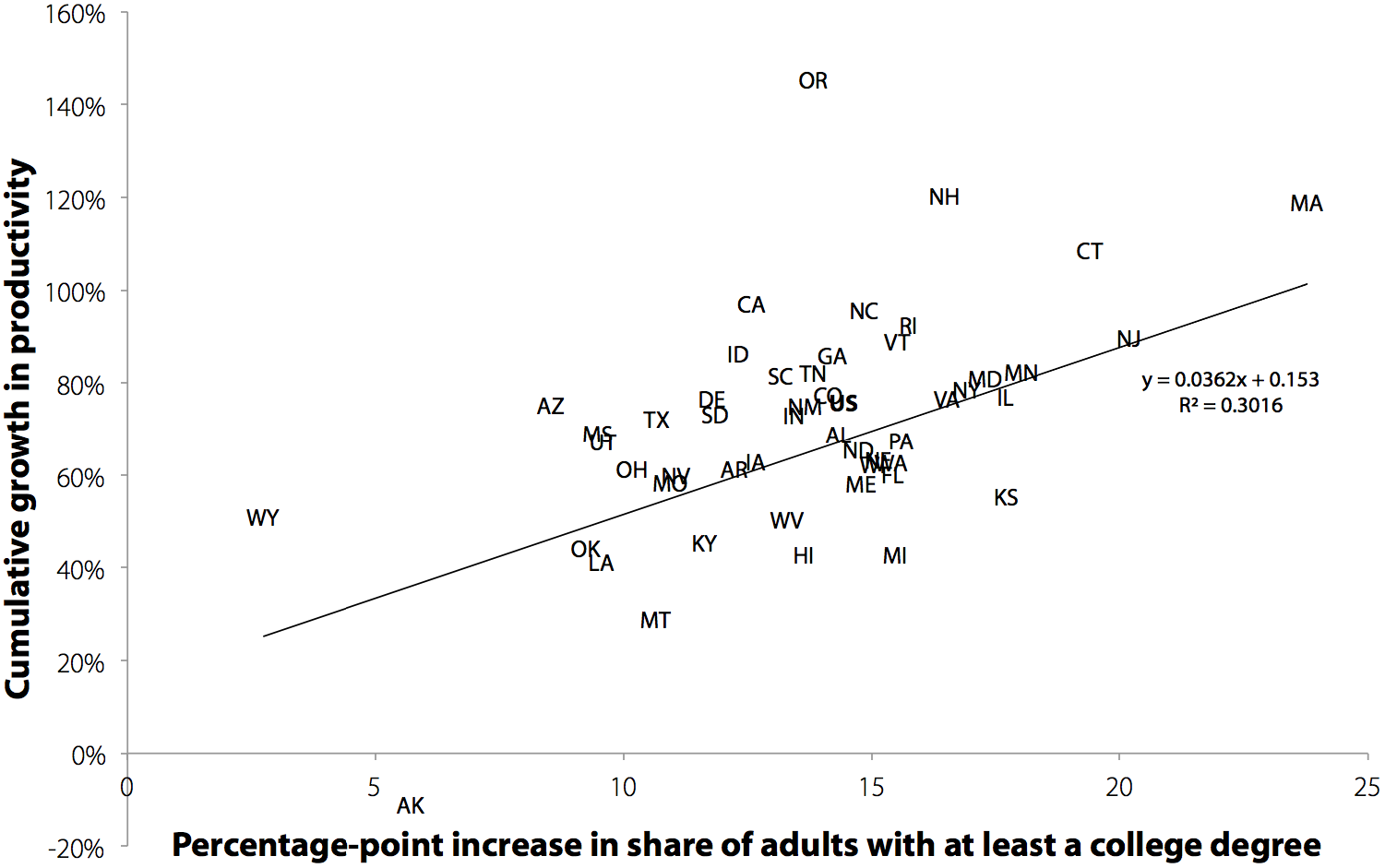

When students receive these kinds of supports, society benefits. As educational attainment increases with investments in schools, so does state economic productivity.3 (See Figure 10.2.)

Source: Berger, N., & Fisher, P. (2013). A well-educated workforce is key to state prosperity. Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute. https://files.epi.org/2013/A well-educated workforce is key to state prosperity.pdf

Two of our highest-achieving states bear this out. Massachusetts assumed its No. 1 ranking in state student achievement—held for more than 2 decades—after adopting a more progressive funding formula in 1993 as a result of litigation. The formula provided additional weights for funding to students from low-income backgrounds and English learners; funding for early childhood programs increased fivefold in the first years of the reforms as well. Importantly, the changes in school funding led to greater investments in educators in high-poverty areas, which research suggests may leverage the largest gains in student performance. The state expanded access to high-quality professional learning for teachers and school leaders and created a program to attract qualified teachers into high-need fields and locations. The state also funds community schools and wraparound supports for students, working in multiple ways to support child health and development.

New Jersey—a state now serving a majority of students of color—ranks No. 2 in the nation on achievement and graduation rates, following a similar school finance reform that began in the late 1990s. It is one of the nation’s top-spending states, with one of the most progressive funding formulas. It allocates roughly 20% more per pupil in districts in which at least 30% of students are in poverty. It changed its funding formula after a series of court decisions starting in the mid- 1990s that called for more equal funding for urban districts serving predominantly low-income families. Funds were allocated to support whole school reform, which included reductions in class size; investments in technology; improvements to facilities; and supports for health, social services, and summer programs to help students catch up. Added resources were directed largely to instructional personnel in the highest-need districts, and there were noticeable improvements to the achievement of all students—including students from low-income families and students of color—on statewide and national tests. One of the most prominent reforms was the funding of 2 years of high-quality, universal preschool for 3- and 4-year-old children in the poorest districts.

Studies show that students who received 2 years of preschool showed sustained and significant achievement gains in 4th- and 5th-grade math, literacy, and science far exceeding those of students who did not experience preschool.

What Policymakers and Educators Can Do

Policymakers at the federal and state levels can use this moment to dramatically increase the equitable allocation of school resources by:

- Allocating federal funds in the recovery acts and, ultimately, in other federal programs in more equitable ways—including supports for the investments in technology, wraparound supports, and educator development that are needed to enable successful education.

- Adopting more equitable state funding formulas and phasing them in as resources return to the system.

- Including preschool in equitable school funding formulas, streamlining sources of funding to ensure that those with greater needs receive the resources that will help them thrive.

Leverage federal funds for equity

In the near term, federal recovery aid can be used to enhance equity at the state and local levels. The federal Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act provided early childhood settings, schools, and districts with nearly $16.75 billion in initial funding to help respond to the crisis. Additional aid is under debate in Congress at the time of this writing. States and districts have an opportunity to use the funds provided through the CARES Act and any subsequent federal aid to invest in strategies that have been shown to advance equity and support the academic success of students.

Federal funds can be used to close the digital divide by purchasing technology (including hardware, software, and connectivity) that supports substantive educational interaction between students and teachers, focusing on the needs of students from low-income families and, for students with disabilities, the use of assistive technology or adaptive equipment. But new devices or internet connections will be of limited effectiveness in closing opportunity gaps if teachers are not supported in learning how to shift their instruction and adapt lessons to a distance learning environment. Technology investments should be paired with investments in research-based professional development on the uses of technology for high-quality learning. Additional school staff, such as guidance counselors and social workers, also need support to learn how to effectively use technology to deliver services to students.

States and districts can also use these funds to invest in wraparound services through community schools, which can serve as an effective long-term strategy for meeting the ongoing academic, health, and wellness needs of our country’s most marginalized students and families. In times of crisis, when the already frayed social safety net is insufficient to meet the basic needs of students and families, these multipurpose schools are stepping in to fill the gap. (See “Priority 8: Establish Community Schools and Wraparound Supports.”) States and districts can use dollars to jump-start the development of community school models that provide health, mental health, and social services to children and families alongside supportive instruction; these funds can also be used to build the infrastructure and expertise for technical assistance to schools implementing this approach, so that a more permanent capacity for meeting students’ needs will exist even after the pandemic is over.

If and when more funds are allocated, it will be critically important for state and local governments to make strategic investments that build local capacity to support all students—and especially the most marginalized—throughout the school year and in times of crisis. These high-impact strategies at the k–12 level include investing in a high-quality teacher workforce in high-need schools (see “Priority 9: Prepare Educators for Reinventing Schools”), especially given the disparities in access to a stable group of well-prepared educators in these schools, which undermines all other reforms that may be attempted.

Looking ahead, the federal government will have opportunities to support these kinds of investments beyond the pandemic through the regular congressional appropriations process, the next reauthorization of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), and administrative action. These opportunities include:

- Expanding and equitably allocating federal education funding across states. The federal government invests less than 2% of its budget across all levels of education and has not maintained its commitments to local schools. For example, the 2002 reauthorization of ESEA promised nearly $26 billion for Title I, Part A programs and school improvement by fiscal year 2007, yet today funding is at $16.3 billion. Title I funding should be substantially increased and allocated more equitably to the states based on pupil needs rather than state spending levels.

- Investing in strategies to close the digital opportunity gap. This includes policies and resources across agencies ranging from the Departments of Education and Commerce to the Federal Communications Commission to ensure access and make investments that provide all schools and households with the technology and the broadband capacity necessary to access information and support learning. To develop a deeper understanding of needs and successful strategies for digital access and instruction, the federal government could establish a national research center to monitor access and track, evaluate, and disseminate successful practices.

- Supporting and providing incentives to states to provide adequate and equitable resources to districts. To ensure school finance reforms are grounded in research-based practices that will deliver adequate and equitable resources, a federal commission on school finance could be established to examine federal, state, and local school funding and provide ongoing research, recommendations, examples, monitoring, and support. A competitive grant program could be designed to support state efforts to restructure their school finance systems and make the shift to a new system.

Adopt more equitable state school funding formulas

Meanwhile, states should be examining how to better account for pupil needs in their funding formulas. One way to do this is to fund schools based on equal dollars per student, adjusted or weighted for specific student needs such as poverty, limited English proficiency, foster care or homeless status, or special education status. In large states, this might be further adjusted for geographic cost differentials, while also taking into account the transportation and other needs of sparse, rural districts.

Use the moment of the economic downturn to support rethinking. While states are in the middle of both a recession and a pandemic, it may sound unrealistic to suggest that now is the time for states to consider changing their school funding system. However, in the past, some states have taken the opportunity to revise their school funding formulas during a recession, with funding flowing into the new formula as it gradually increases.

There are at least two reasons why a state may want to consider changing its funding formula now:

- Formulas will be changing in most states anyway: As states start to adjust their school funding to take into account reduced revenue, they will most likely be making changes to their education funding system. The changes that states will be making are born out of a necessity to cut—not on a plan to help students. If major changes will happen anyway, it may be possible to design some of them to aid students in the longer term, even if the change will take some time to implement.

- Eventual growth in funding will help to raise all ships, making change easier: Some states wait to change their funding system until they have additional dollars to do so. However, some states have found that the best time to change their funding system is when they have hit the bottom of an economic cycle. Once state budgets begin to improve, and as new money eventually flows to schools, a revised formula could ensure that all districts receive increased funding while those with greater need receive more.

Maryland adopted a new funding formula in 2002, during the post-9/11 economic downturn. The formula, enacted in the Bridge to Excellence in Public Schools Act, was designed to provide districts with more adequate and equitable funding while implementing a new assessment and accountability system. The formula increased state spending on education and also equalized funding based on a district’s wealth and targeted more funding to high-need student groups. The Bridge to Excellence in Public Schools Act also reshaped accountability around the state’s new learning standards, eventually leading to comprehensive yearly master plans that describe “the goals, objectives, and strategies that will be used to improve student achievement,”4 and increased the number of students meeting state and local performance standards. Maryland’s achievement on the National Assessment of Educational Progress increased sharply in reading and math over the following decade, with reduced achievement gaps. Although the rate of improvement slowed during the cutbacks of the Great Recession, the state has just enacted another round of equity-oriented funding reforms.

Rhode Island acted to adopt a new school funding formula in 2010, in the immediate wake of the Great Recession. The new formula was designed to provide more significant equity in the school funding system while also aligning with the state’s preexisting accountability system, known as the Basic Education Program. According to a report from the Center for American Progress, the formula was implemented without any additional funding initially. Instead, all districts were held harmless from financial loss for up to 10 years. As new funding became available, it was slowly distributed through the new formula. This slow phase-in approach created relatively little political discord, and 70% of students ultimately received more state aid. In the wake of the formula change, the state’s 4th- and 8th-grade students climbed from below to above the national average in reading achievement and saw modest gains in math.

California is another case in point. In 2013, after years of severe budget cuts, and while still experiencing the effects of the Great Recession, California began to implement a new, more equitable Local Control Funding Formula (LCFF) with a plan for achieving targeted funding increases over 8 years—a span of time that was ultimately shortened when the economy improved. (Full funding was achieved by 2018–19.) The plan:

- eliminated the majority of the state’s categorical programs;

- instituted uniform per-pupil “base” grants to school districts, charter schools, and county offices of education, adjusted by grade level;

- created “supplemental” grants equal to 20% of the adjusted base grant for each English learner, student in foster care, and student from a low-income family; and

- established “concentration” grants for local education agencies with enrollments of more than 55% English learners, students in foster care, and students from low-income families. Students who meet more than one eligibility criteria are only counted once.

The new formula allocated billions of new dollars to districts serving high-need students and provided all districts with broad flexibility to develop—in partnership with parents, students, and staff—spending plans aligned to state and local priorities and needs. As part of these Local Control and Accountability Plans, districts must annually evaluate student progress for all student groups in relation to the state’s eight priorities, expressed in a multiple-measures accountability system that takes into account key inputs (such as rich curriculum, positive climate, and qualified educators) as well as a range of outcomes (attendance, graduation rates, and college and career readiness, as well as tested achievement). Budget decisions must be made transparently and reported in terms of how they will move the needle on these important priorities for all students.

These structural reforms coincided with the state’s implementation of the Common Core State Standards and Next Generation Science Standards, implementation of the Smarter Balanced Assessment System, and development of new educator preparation and licensure standards to support the more rigorous academic goals. Within only a few years, the LCFF positively impacted student outcomes, especially for students from low-income families, and shrank achievement gaps. These results showed up in significant gains for the state’s students on the National Assessment of Educational Progress as well, moving the state from 48th and 49th in reading and math, respectively, to near the national average in reading and halfway to the national average in math.

In this past year, California also used an equity-based formula similar to the LCFF to allocate $5.3 billion in additional federal funds to schools, going well beyond the portion of the CARES Act specifically identified for k–12 education, thus doubling down on equity and seeking to maintain the gains it has achieved.

Use equity principles to allocate funds within districts and schools. Once funding reaches districts, it is also important for it to be spent equitably to meet student needs. A key principle of continuous improvement is that it requires continuous transparency. In California, districts must explain in their Local Control and Accountability Plans how they will use their supplemental and concentration grant funding to meet the needs of the students who generated the funding. In Los Angeles Unified School District, community advocates proposed an Equity Index, which is now used to help guide those allocations to the schools with the highest needs.

Include preschool in school funding formulas

Another key change that states can make to promote equity is to add preschool to their school funding formulas. Two states, Oklahoma and West Virginia, have school funding formulas that fund preschool for 4-year-olds as an additional grade of school.5 The District of Columbia funds preschool for 3-year-olds as well as 4 year-olds through its formula, with an additional weight that accounts for the higher staffing levels needed for young children. These states have some of the highest levels of enrollment in preschool or Head Start in the country, with 69% of all 4-year-olds served in West Virginia and 85% in both Oklahoma and Washington, DC.6 West Virginia was able to add preschool to its funding formula in 2002, in the midst of the post-9/11 downturn, despite the legislature’s concerns about the cost. Policymakers did so by agreeing to a 10-year phase-in period and tying the agreement to a larger bill related to k–12 school funding.

The funding changes in California, Maryland, and Rhode Island have all led to increased equity in their education finance systems over time (see Figure 10.3). As revenue increased in states after the recession, the new funding formulas were able to close the gap between wealthy and poor districts. Education Week’s annual Quality Counts report showed that all three states’ finance systems warranted increased equity scores between 2014 and 2020, with each of them now having scores that exceed the national average.

Note: Education Week calculates equity scores using a combined indicator of the degree to which a school district’s revenue is correlated with property wealth, per-pupil expenditures below the state median, the level of variability in funding across a state, and the difference between the 5th and 95th percentile of districts.

Data Source: Education Week Quality Counts School Finance Report Cards.

In sum, changing how we fund schools is never easy, and it might seem like it is an impossible task during a recession. However, this pandemic has raised equity issues to a new level of consciousness that may allow innovative policy responses to emerge in many contexts, from preschool through high school. In the past, some states have changed their systems during difficult economic times in ways that have led to improved equity and adequacy in funding while also supporting strategies for higher student achievement. While it may appear to be counterintuitive on the surface, policymakers should take advantage of this recession to redesign both federal aid and state and local funding systems.

Resources

» View the entire resource library

Endnotes

- Evans, W. N., Schwab, R. M., & Wagner, K. L. (2019). The Great Recession and public education. Education Finance and Policy, 14(2), 298–326.

- Jessen-Howard, S., & Workman, S. (2020). Coronavirus pandemic could lead to permanent loss of nearly 4.5 million child care slots. Washington, DC: Center for American Progress.

- Berger, N., & Fisher, P. (2013). A well-educated workforce is key to state prosperity. Washington, DC: Economic Policy Institute. https://files.epi.org/2013/A%20well-educated%20workforce%20is%20key%20 to%20state%20prosperity.pdf.

- Maryland State Department of Education and Office of Finance. (2018). Maryland’s reform plan bridge to excellence in public schools: 2018 guidance annual update. Baltimore, MD: Author. (p. iii). http://marylandpublicschools.org/about/Documents/DSFSS/BridgeExcellence/ TPCPT2018/2018BridgeExcellenceAnnualUpdateGuidance.pdf.

- Maine also includes preschool in its school funding formula, but programs are run for a minimum of just 2 hours, so preschool funding per pupil is low compared to k–12; Barnett, W. S., & Kasmin, R. (2016). Funding landscape for preschool with a highly qualified workforce. Washington, DC: National Institute for Early Education Research. https://sites.nationalacademies.org/cs/groups/dbassesite/documents/webpage/ dbasse_175816.pdf.

- Friedman-Krauss, A. H., Barnett, W. S., Garver, K. A., Hodges, K. S., Weisenfeld, G. G., & DiCrecchio, N. (2018). The state of preschool 2018. New Brunswick, NJ: National Institute for Early Education Research.