Downloads

Priority 4: Ensure Supports for Social and Emotional Learning

I’m concerned about food, jobs, money, my education. Racism toward Asian Pacific Islander folks is a big concern for us too. I miss being around my friends, and I’m feeling really, really depressed, but I can’t really tell my family.

What Students Need

Recent data indicate that young people are experiencing chronic stress and trauma as they navigate basic needs and health concerns, a lack of connectivity to their school communities, and exhaustion from constant anxiety about the future. The pandemic has been disruptive for nearly everyone but has also exposed and exacerbated existing inequities, including those in health and safety, mental health, and learning opportunities and experiences. As one middle school teacher described, although her students were hungry to learn, they faced many barriers to participation:

Many of my students are refugees, fleeing violence in their home countries, children who have been separated from their families, and longtime English language learners…. My students fight a silent battle against inequity every day. Distance learning has made this battle so much harder.

In order to buffer a generation of children and youth from the negative impacts of these cumulative inequities, schools need to nurture the whole child by intentionally integrating social and emotional learning. As part of this effort, in this moment of deep trauma converging with deep awareness of racial injustice, children and youth need their schools to dismantle practices that have perpetuated systemic racism, including discriminatory discipline practices that have too often criminalized and marginalized children of color. These should be replaced with restorative practices that help students get the help they need while acquiring the social and emotional skills, habits, and mindsets necessary to be successful in school and in life.

The science of learning and development, which builds on rich developments over the past 2 decades, helps us see that academic, social, and emotional learning are interrelated and reinforcing and that learning is inherently social and emotional.1 For instance, children and youth learn best when they feel safe, find the information to be relevant and engaging, are able to focus their attention, and are actively involved in learning. This requires the ability to combine skills of emotion regulation and coping strategies with cognitive skills of problem-solving and social skills, including communication and cooperation.

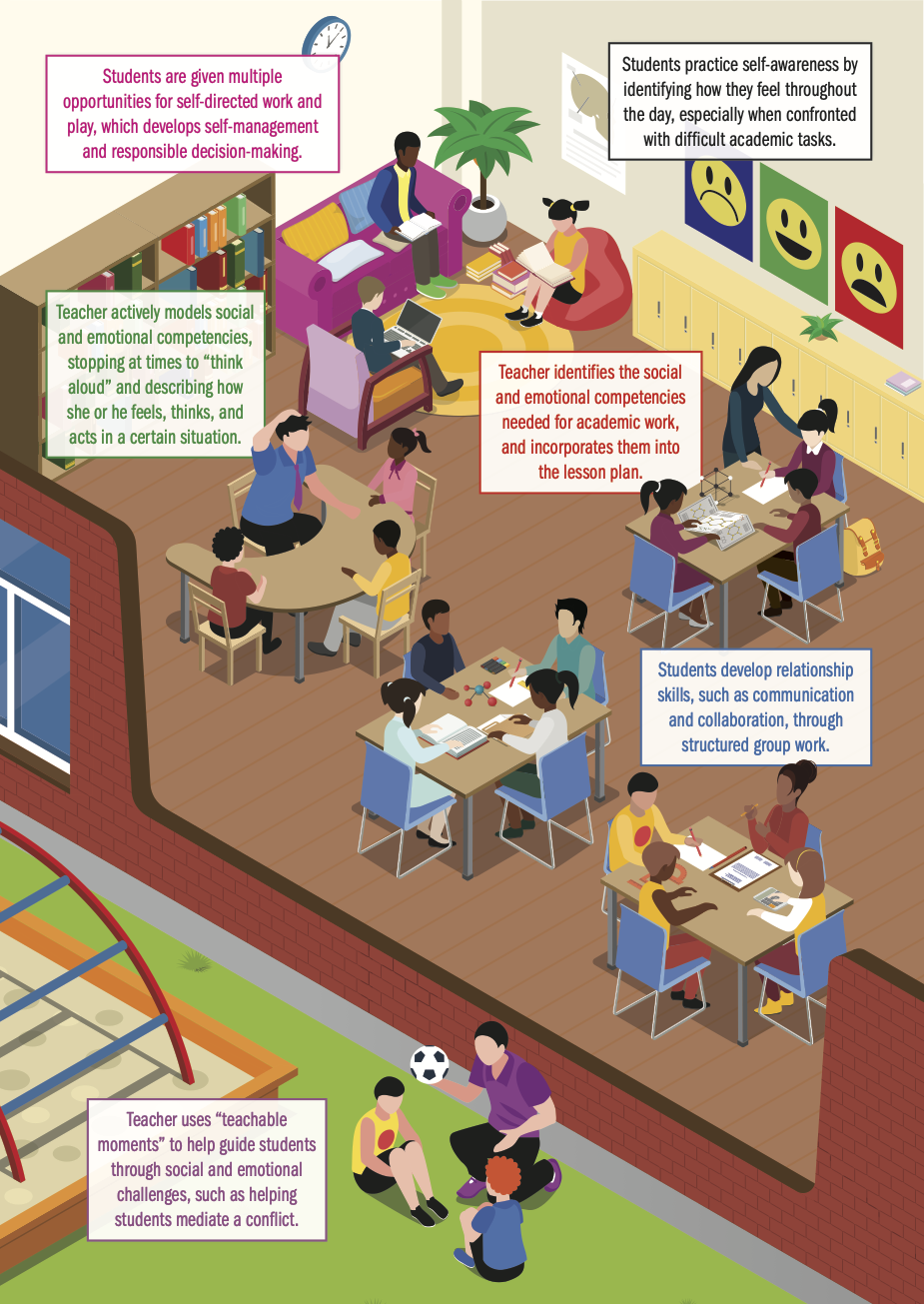

Studies show that sustained and well-integrated social and emotional learning (SEL) programs can help schools engage their students and improve achievement. Explore the classroom practices that make up the best and most effective SEL programs.

Source: Edutopia

Attitudes, beliefs, and mindsets also matter for school and life success. Educators and school personnel play an important role in shaping students’ beliefs about their own abilities, their sense of belonging, and their academic mindset. Self-efficacy is enhanced by a student’s confidence that effort increases competence. A growth mindset enables students to engage more productively in academic and personal pursuits. All of these are supported by an inclusive learning environment that uses educative and restorative approaches to support behavior rather than relying on punitive methods that exclude and discourage students.2

The pandemic, economic uncertainty, and heightened awareness of long-standing racial injustices have made it abundantly clear that children and youth need an adaptive and responsive school system that supports them to fully develop their social and emotional capacities and leverages children’s assets to strengthen their learning and well-being.

What Policymakers and Educators Can Do

With support from state and local education leaders, educators have an opportunity as schools and communities restart, recover, and reinvent to prioritize policies and practices that are immediately responsive to students’ and adults’ social and emotional needs while building capacity for a whole child approach going forward.

Implement a comprehensive system of support

Effective school environments take a systematic approach to promoting children’s social, emotional, and academic well-being in all facets of school life and in connections to the community. Students’ personal responses to the pandemic, economic crisis, and racial injustices may vary widely, and some students may need targeted or intensive supports.

CASEL’s SEL roadmap for reopening school recommends that schools develop an “adaptive and responsive system of tiered supports that leverages students’ assets to help them cope, navigate and strengthen their social and emotional competencies.” As schools learn about and identify the strengths and needs of students, they will need clear processes (e.g., screeners, referrals) and structures (e.g., tiered, integrated systems of support) for school staff to work with families and partner with school-employed or community-based mental health and trauma professionals to connect students with additional targeted (tier 2) or intensive (tier 3) supports to meet their needs. (See, for example, North Dakota’s well-developed resources for multi-tiered systems of support.)

This may include counseling and additional behavioral, mental health, or trauma supports; it may also include providing connections to food, housing, technology, transportation, or other resources. (See “Priority 8: Establish Community Schools and Wraparound Supports” for more on integrated supports and services.) Schools must ensure that these processes avoid labeling students and do not rely on assumptions about students based upon their race, their language, or their socioeconomic status.

Ensure opportunities for explicit teaching of social and emotional skills at every grade level

While a whole-school approach to social and emotional learning is necessary, schools also need to set aside a time and place to focus explicitly on social and emotional skill building.3 By explicitly teaching the interrelated set of cognitive, social, and emotional competencies that underscore the way people learn, develop, maintain mutually supportive relationships, and become psychologically healthy, educators can ensure that students and staff have tools for both the short term and long term. Teaching students how to recognize and manage their emotions, access help when they need it, and learn problem-solving and conflict resolution skills makes schools safer. A meta-analysis of more than 200 studies found that schools using SEL programs reduced bullying and poor behavior while supporting increased school achievement.

Locate a place in the curriculum and school day in which students and educators can develop and practice key skills and competencies. In early childhood education and preschool programs, this may take place through scripted stories and books, and intentional activities embedded throughout the day. In elementary classrooms, this might take place in morning meetings or another dedicated block in the day. In middle and high schools, this can take place in advisories. (See “Priority 5: Redesign Schools for Stronger Relationships” for more detail.)

Baltimore City Public Schools built upon existing SEL implementation efforts and developed SEL lesson plans aligned with grade groupings and weekly themes around compassion, connection, and courage.

By giving young students the tools to self-regulate, this preschool in New Orleans boosts their readiness to learn.

Source: Edutopia

Put it Into Practice

Addressing Students’ Developmental Needs During Transition

Students go through many transitions from early childhood to young adulthood, such as the annual return from summer break or the transition from middle to high school. What happens during these transitions, and the degree to which students’ developmental needs are met, influence their social and emotional competencies and long-term success. To help students with the important transition into this coming school year, identify ways to meet their developmental needs. For example:

- In early childhood programs: Provide young children with simple strategies for exploring, discussing, and regulating their emotions. Read alouds offer an easy way to prompt conversations about how big changes make them feel.

- In elementary school: Support students in developing relationship-building and conflict-resolution skills by helping them co-create shared agreements for their new class or distance learning environment.

- In middle school: Offer adolescents an opportunity to reconnect and create a sense of closure from the previous school year, such as by writing letters to their former classmates or teachers, or discussing with peers how the last few months will impact their perspectives as they enter a new grade.

- In high school: Provide older students with a way to reflect on and document their experience and what they’ve learned about themselves during the pandemic, either through journal writing, artwork, music, or other creative outlets.

For more practices, review the SEL Providers Council website.

Develop or adopt an SEL program. Schools may develop their own approach or adopt an evidence-based SEL program. However, adopting a program is not enough to ensure positive outcomes. To be successful, educators need ongoing support beyond an initial training (e.g., coaching, follow-up training). It is important that administrators and school leaders support the effective implementation of SEL programs by setting high expectations and allocating resources for programming.4 School leaders who model the use of SEL language and practices and endorse the use of SEL practices throughout the school create a schoolwide climate for SEL.

States and districts can support the adoption and implementation of social and emotional learning by establishing SEL curriculum specialists in leadership positions to support sustainable use of SEL activities for students, educators, and families. School-based SEL coalitions of educators, community organizations, and families, supported by these district specialists, can ensure the creation and high-quality implementation of SEL supports based on local needs of staff and students in every grade. In its reopening plan, Oregon emphasizes the need to incorporate multiple non-dominant voices in such coalitions and to formalize an SEL lead for each school.

It is important to prevent potential equity pitfalls by avoiding a deficit mindset that assumes that the purpose of SEL is to develop skills that some students do not possess and to underemphasize the meaningful development of student agency. Because social and emotional competencies can be expressed differently across cultures, if leaders and educators implement SEL without an appreciation of similarities and differences, with an underemphasis on student agency, some students may feel more alienated. The National Equity Project has developed guidance with recommendations to prevent such pitfalls, as has CASEL, which offers a five-part webinar series.

Consider using mindfulness strategies. The use of mindfulness strategies and other techniques for calming oneself, as well as monitoring and redirecting attention, also shows benefits for learning and stress management.5 Mindfulness practice—which cultivates greater awareness of one’s experience infused with kindness6—and related contemplative practices have also been linked to greater social and emotional competencies, including capacities for regulation, as well as reductions in stress and implicit bias.7 Mindfulness strategies can be integrated into instruction to include educators and school staff to support their self-care and stress management abilities. Pure Edge provides several free tools that have been adopted by districts such as Jackson, MS, and Philadelphia, PA; and by entire states, including Delaware and Rhode Island.

Infuse social and emotional learning into instruction in all classes

Students need opportunities to develop social and emotional skills throughout their school day. Research shows that when SEL opportunities are embedded throughout the school day and integrated into other subject matter, the benefits are even more pronounced.8 Capitalizing on teachable moments reinforces and provides more opportunities for children to practice the skills they are learning through explicit SEL instruction.

Integrate SEL skills into curriculum and instruction. Schools and educators that have not already been working to infuse SEL skills into their academic instructional practice may feel daunted by the task and be unsure of how to do it, but there are helpful resources readily available. For example, Facing History and Ourselves, EL Education, and Transforming Education have tools and curricula that include embedded SEL components. Resources based on the science of learning and development are also available from the National Commission on Social, Emotional, and Academic Development, CASEL, and Greater Good Science Center.

At Lakewood Elementary School in Sunnyvale, CA, teachers and leaders understand that SEL should be integrated into every aspect of the school, from explicit classroom instruction and infusion into academic content to school climate and culture (see Figure 4.2).9 Teachers at Lakewood use strategies such as the Chillax Corner, which offers space and activities for students to regulate their emotions when upset; building relationships through team-building exercises; and collaborative academic work that allows students to put into practice social and emotional competencies such as active listening, understanding others’ perspectives, and resolving disagreements.

Source: Melnick, H., & Martinez, L. (2019). Preparing teachers to support social and emotional learning: A case study of San Jose State University and Lakewood Elementary School. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute.

Washoe County School District in Nevada is creating weekly distance learning plans incorporating practices for all grade levels to continue students’ in-school SEL lessons at home. These efforts are connected to longer-term investments in SEL curriculum and professional development the district began making prior to the pandemic. For instance, Washoe developed and trained SEL lead teams, composed of school staff, to share and debrief data on school climate and on students’ social and emotional skills, habits, and mindsets. The district also developed early warning indicators of students at risk of dropping out of school to look at trends in the data to inform student engagement efforts. These efforts have included student data summits that district leaders believe have led to greater student engagement and empowerment.10 As a result, in partnership with WestEd and the Regional Educational Laboratory West (REL West), Washoe County School District developed a toolkit of student engagement exercises to gather data and analyze student experiences.

All educators can play an active role in co-regulating students’ behaviors by providing them with a repertoire of words and strategies to use in different situations to help them develop their self-regulation skills. For example, teachers might use disagreements as opportunities to help students practice conflict resolution by walking students through a structured, stepwise process that involves calming techniques, turn-taking (in which each student acknowledges the other’s perspectives and emotions), and collaborative solution development. As a component of the school’s advisory class, Social Justice Humanitas Academy in Los Angeles uses councils to build community and create space for “the practice of listening and speaking from the heart.” During councils, students and teachers take turns sharing the positive and difficult things happening in their lives while sitting together in a circle. North Dakota’s reopening plan specifically suggests expanding advisory classes to better meet current needs.

It is important that teaching for self-regulation not be implemented in ways that suggest that students cannot fully express their emotions or demonstrate their feelings, or that students should exhibit equanimity in the face of trauma and injustice. Concerns have emerged that some interpretations of SEL have been used to undermine student expression, to manage student behavior in ways that are culturally insensitive, and, in some cases, to extend policing into interactions around students’ emotional self-expression.

Provide guidance and support to develop students’ executive functions and productive mindsets. In addition to emotional awareness and specific skills for handling emotions and engaging in prosocial behavior, there are a set of habits and mindsets that can have a powerful effect on students’ learning and achievement. Holding a growth mindset and connecting academic endeavors to personal values supports learning and helps students persevere in the face of challenges. Four key mindsets have been identified as conducive to perseverance and academic success for students:

- Belief that one belongs at school

- Belief in the value of the work

- Belief that effort will lead to increased competence

- Sense of self-efficacy and the ability to succeed11

The types of messages conveyed by teachers and schools and corresponding attitudes may be especially relevant with adolescents whose self-perceptions and perceptions about school have a strong effect on their motivation and behavior. Effective programs that promote stronger learning for adolescents involve creating climates in which adolescents feel respected, affirmed, and challenged with the opportunity to improve through feedback, supports, and chances to revise their work.12

Institute restorative practices

End zero-tolerance policies and exclusionary discipline. SEL programs cannot enable meaningful long-term growth for students in environments that are otherwise authoritarian, punitive, and exclusionary, rather than educative and inclusive. Zero-tolerance policies that were widespread in many states and districts have led to high rates of suspension and expulsion that have also proved to be discriminatory, with students of color and students with disabilities disproportionately excluded from school. Evidence shows that this is not because of worse behavior but because of harsher treatment for minor offenses, such as tardiness, talking in class, and other nonviolent behavior.

Rather than teaching students how to change their behavior, exclusionary punishment undermines student learning and attachment to school and increases the chances of students dropping out. Even one suspension can double the odds of a student dropping out, feeding the school-to-prison pipeline, which for some children begins in preschool.

In this moment, as many schools are considering eliminating the police presence in schools that has often been associated with harsh punishments for trivial offenses and criminalization of children of color, it is essential to replace police with restorative practices, rather than leaving a vacuum. As Tiana Lee, the Alternatives to Suspensions Specialist at Brooklyn Center High School, described:

The impacts of suspensions were clear: our neediest students were falling further behind and excluding them did little to improve their behavior. But simply ending suspensions was not enough, as we had still not begun to address the root causes of students’ misbehavior.

Accumulating research evidence suggests that shifting to restorative practices reduces the use of exclusionary discipline, resulting in fewer and less racially disparate suspensions and expulsions while also making schools safer, improving school climate and teacher–student relationships, and improving academic achievement.13 Restorative practices enable educators and school leaders to understand how they may unintentionally trigger or escalate problem behavior; these practices help students and staff cultivate strategies for resolving conflict and creating healthier, more positive interactions.14

Adopt equity-oriented restorative practices that enable students to solve problems. Restorative justice practices support the overarching goal of strengthening school climate by developing a restorative mindset in adults that allows them to establish and sustain relationships and build a sense of community that is a precursor to community members’ understanding that violating community norms harms their community. Central to a restorative justice approach is the belief that all people have worth and that it is important to build, maintain, and repair relationships within a community.15

Relationships and trust are supported through restorative practices, including universal interventions such as daily classroom meetings in which students and staff regularly share experiences and feelings, community-building circles, and conflict resolution strategies. These are supplemented with restorative conferences when a challenging event has occurred, often managed through peer mediation. A restorative justice approach deals with conflict by identifying or naming the wrongdoing, repairing the harm, and restoring relationships. As a result, restorative discipline is built on strong relationships and relational trust, with systems for students to reflect on any mistakes, repair damage to the community, and get counseling when needed. Creating an environment in which students learn to be responsible and are given the opportunity for agency and contribution can transform social, emotional, and academic behavior and outcomes.

The more comprehensive and well-infused the approach, the stronger the outcomes. For example, a continuum model including proactive restorative exchanges, affirmative statements, informal conferences, large-group circles, and restorative conferences substantially changed school culture and outcomes rapidly in one major district, as disparities in school discipline were reduced every year for each racial group, and gains were made in academic achievement across all subjects in nearly every grade level.16

At the school level, Bronxdale High School in New York City illustrates what can happen when a comprehensive program of equity-oriented educative and restorative behavioral supports is put in place. An inclusion high school that serves a disproportionate population of students with disabilities in a low-income community of color, the once chaotic and unsafe site is now a safe, caring, and collaborative community in which staff, students, and families have voice, agency, and responsibility. At Bronxdale, community building—accomplished through SEL work in advisories, student-designed classroom constitutions, and supportive affirmations and community development in all classrooms—is integral to the now successful restorative approach. As Bronxdale Principal Carolyn Quintana described, restorative practices have value only when there is something to restore and that something is “the community, relationships, and harmony.”17 Restorative deans support the building of community and implementation of a restorative justice approach; teaching students behavioral skills and responsibility; and repairing harm by making amends through restorative practices such as peer mediation, circles, and youth court. Their work is also supported by teachers, social workers, counselors, and community partners who are part of the school’s multi-tiered system of support (MTSS) that enables trauma-informed and healing- informed supports for students.

Now a demonstration site for restorative justice in New York City, Bronxdale is known for its low suspension rate and strong academic program and results. Although most of its 445 students enter Bronxdale performing far below proficiency levels on standardized tests, they leave having outperformed their peers in credit accrual, 4- and 6-year graduation rates, and enrollment in postsecondary education.

Importantly, restorative practices can be implemented at all grade levels. Building community and supporting children by teaching them the skills to resolve conflicts and repair harm can begin in early childhood. For example, Oakland Unified School District (OUSD) in California has been scaling implementation of its restorative justice program since 2007. Glenview Elementary School in OUSD is one of the schools implementing schoolwide restorative justice practices, and one of its key strategies is the use of dialogue circles (illustrated in this video) to check in, settle disputes, teach skills, and build community.

At Glenview Elementary School, dialogue circles are part of a program aimed at building collaboration, respect, and positive behavior among students.

Source: Edutopia

Enact policies that enable social and emotional learning and restorative practices

Adopt standards and guidance for SEL and restorative practices. Throughout this pandemic and beyond, states and districts can support schools by developing clear guidelines and standards for children’s learning and development in these domains. Standards can span preschool through grade 12 and specify the social and emotional skills children should be able to demonstrate, describe how to promote those competencies in children, and specify the conditions and settings that cultivate these competencies. They can also specify the necessary preparation and ongoing professional learning for educators to infuse social and emotional skills into all school experiences.

Washington state has worked to develop and implement social and emotional learning standards, benchmarks, indicators, and a constellation of professional learning resources, including an SEL Online Education Module that covers trauma-informed, restorative, and culturally responsive and affirming practices as well as promoting social awareness, relationships skills, self-awareness, self-management, and responsible decision-making skills.

Illinois and Minnesota are two states that have developed restorative practice guidance and resources for schools. Minnesota has developed a suite of resources, including key principles to guide restorative practices in schools and implementation guidance to provide school districts, administrators, and educators with resources to integrate restorative practice into schoolwide climate, discipline, and teaching and learning. The key principles, each of which has corresponding practices, include:

- Principles that develop a restorative mindset—including putting relationships first and providing support and accountability so that those in positions of authority (teachers, staff, and administrators) do things with students rather than to or for them;

- Principles for just and equitable learning communities—including the belief that history, race, justice, and language matter; that interconnection and innate goodness matter; and that balancing relationship building and problem-solving in the process matters; and

- Principles of just and equitable discipline—including emotional literacy and discipline as guidance to repair harm, make amends, and give back to the community.

The Dignity in Schools Campaign has developed a model code and several additional resources that provide recommended language for alternative policies to pushout and zero-tolerance policies. The campaign’s guidance supports removing police from schools and replacing them with effective staff-led strategies for classroom management, conflict resolution, and mediation. When staff lack strategies for managing behavior, focused supports may be needed. Using class-level data to provide targeted professional development for teachers may also be effective.

Provide funding and supports for curriculum resources and professional development. States such as Minnesota and cities such as Cleveland, OH, have developed curriculum resources for educators to infuse social-emotional skills into school experiences and have funded counseling and wraparound supports that enable children to cope with the many challenges they are experiencing.

State agencies and districts can use ESSA funds as well as federal stimulus funds from the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act to support SEL programs and teacher training in SEL. (See “Priority 10: Leverage More Adequate and Equitable School Funding” for more detail on how to leverage federal funding.)

School leaders can also create working conditions (e.g., time and space for professional learning and self-care) that help adults feel connected, empowered, and valued. Studies have found that efforts to support SEL are strongest when they are conducted by school personnel who have opportunities to support and deepen their own skills,18 which highlights the critical need for ongoing professional development as a vital element for promoting these capacities in students. Districts can take advantage of hybrid learning schedules that allow for a transition day between cohorts to dedicate more time to professional development and collaboration.

Professional learning should focus on trauma-informed SEL practices; culturally responsive, affirming, and anti-racist practices; restorative justice; and the promotion of social and emotional competencies for educators and school leaders to engage in self-care in order to respond to the needs of students. Organizations such as Sanford Inspire, part of Sanford Harmony at the National University System, and the Friday Institute at North Carolina State University have developed free courses to support educators in building their capacity to support SEL and their own social and emotional skills. The American Federation of Teachers (AFT) has also developed professional learning resources and lessons to support educators’ capacity for SEL-informed and trauma-informed practices.

Resources

» View the entire resource library

Endnotes

- Darling-Hammond, L., Flook, L., Cook-Harvey, C., Barron, B. J., & Osher, D. (2019). Implications for educational practice of the science of learning and development. Applied Developmental Science, 24(2), 97–140. https://doi.org/10.1080/10888691.2018.1537791.

- Darling-Hammond, L., & Cook-Harvey, C. M. (2018). Educating the whole child: Improving school climate to support student success. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute.

- Greenberg, M. T., Domitrovich, C. E., Weissberg, R. P., & Durlak, J. A. (2017). Social and emotional learning as a public health approach to education. Future of Children, 27(1), 13–32; Hamedani, M. G., & Darling- Hammond, L. (2015). Social emotional learning in high school: How three urban high schools engage, educate, and empower youth. Palo Alto, CA: Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education. https://edpolicy. stanford.edu/library/publications/1310.

- Durlak, J. A., Weissberg, R. P., Dymnicki, A. B., Taylor, R. D., & Schellinger, K. B. (2011). The impact of enhancing students’ social and emotional learning: A meta-analysis of school-based universal interventions. Child Development, 82, 405–432.

- Zenner, C., Herrnleben-Kurz, S., & Walach, H. (2014). Mindfulness-based interventions in schools: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Frontiers in Psychology, 5(603).

- Mind and Life Education Research Network. (2012). Contemplative practices and mental training: Prospects for American education. Child Development Perspectives, 6, 146–153.

- Schonert-Reichl, K., & Roeser, R. W. (2016). “Mindfulness in Education: Introduction and Overview of the Handbook” in Schonert-Reichl, K., & Roeser, R. W. (Eds.). Handbook of Mindfulness in Education: Integrating Theory and Research Into Practice (pp. 3–16). New York, NY: Springer.

- Jones, S. M., & Bouffard, M. B. (2012). Social and emotional learning in schools: From programs to strategies. Social Policy Report, 26(4), 1–33.

- Melnick, H., & Martinez, L. (2019). Preparing teachers to support social and emotional learning: A case study of San Jose State University and Lakewood Elementary School. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute.

- Darling-Hammond, L., & Cook-Harvey, C. M. (2018). Educating the whole child: Improving school climate to support student success. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute.

- Farrington, C. (2013). Academic mindsets as a critical component of deeper learning [Whitepaper]. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Consortium on Chicago School Research.

- Dweck, C. S. (2017). Mindset - Updated Edition: Changing the Way You Think to Fulfill Your Potential. New York, NY: Brown, Little Book Group; Yeager, D. S., & Walton, G. M. (2011). Social-psychological interventions in education: They’re not magic. Review of Educational Research, 81(2), 267–301.

- Augustine, C. H., Engberg, J., Grimm, G. E., Lee, E., Wang, E. L., Christianson, K., & Joseph, A. A. (2018). Can restorative practices improve school climate and curb suspensions? An evaluation of the impact of restorative practices in a mid-sized urban school district. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR2840.html; Fronius, T., Darling-Hammond, S., Sutherland, H., Guckenburg, S., Hurley, N., & Petrosino, A. (2019). Restorative Justice in U.S. Schools: An Updated Research Review. San Francisco, CA: WestEd. https://www.wested.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/resource-restorative-justice-in-u-s-schools-an-updated-research-review.pdf; Gregory, A., Clawson, K., Davis, A., & Gerewitz, J. (2016). The promise of restorative practices to transform teacher–student relationships and achieve equity in school discipline. Journal of Educational and Psychological Consultation, 26(4), 325–353.

- Losen, D. J. (2015). Closing the Discipline Gap: Equitable Remedies for Excessive Exclusion. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- Evans, K., & Vaanering, D. (2016). The Little Book of Restorative Justice in Education: Fostering Responsibility, Healing, and Hope in Schools. New York, NY: Good Book.

- Gonzalez, T. (2015). “Socializing Schools: Addressing Racial Disparities in Discipline Through Restorative Justice” in Losen, D. J. (Ed.). Closing the Discipline Gap: Equitable Remedies for Excessive Exclusion (pp. 151–165). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

- Ancess, J., Rogers, B., Duncan Grand, D., & Darling- Hammond, L. (2019). Teaching the way students learn best: Lessons from Bronxdale High School. Palo Alto, CA: Learning Policy Institute. (p. 25).

- Weissberg, R. P., Durlak, J. A., Domitrovich, C. E., & Gullotta, T. P. (2015). “Social and Emotional Learning: Past, Present, and Future” in Durlak, J. A., Domitrovich, C. E., Weissberg, R. P., & Gullotta, T. P. (Eds.). Handbook of Social and Emotional Learning: Research and Practice (pp. 3–19). New York, NY: Guilford.